Archives: Content

Newsletter Video 3

Newsletter Video 2

Here’s a hand that requires good thought process.

Preempts

The most valuable asset in a bridge auction is space. When the hand belongs to us, we want to preserve space, giving us as much room as possible to communicate and explore. More room means more possibility to find fits, exchange information, and make informed decisions about how high to bid. We use conventions like 2/1 GF, Fourth Suit Forcing, Jacoby 2NT, and Inverted Minors to keep the bidding low when we have strong hands.

Because we want to preserve bidding space when we have good hands, we also want to take up space when the hand belongs to the opponents. Crowding the auction makes it much more difficult for the opponents to exchange information and make good decisions. That’s the idea behind preempts.

Of course, the opponents can double us, so we can’t go crazy and bid at the 4- or 5-level with a flat Yarborough. We need the right kind of hand to preempt.

There are hands that have a lot more offensive potential than defensive potential. These are distributional hands with a long suit (or sometimes two suits). When this sort of hand gets to pick the trump suit, it can take many more tricks than its HCP total would suggest; when something else is trumps, its trick-taking potential goes down (because the honors in its long suit are less likely to cash). We refer to this concept as ODR: Offense to Defense Ratio.

Let’s look at an example:

♠ KQJT962 ♥ 4 ♦ 832 ♣ 74

This is a classic hand for a preempt. With spades as trumps, this hand will take 6 tricks, even if partner contributes nothing. With anything else as trumps, this hand will probably take no tricks, since it’s unlikely a second round of spades will cash. This sort of hand provides safety in preempting because if the opponents double you, you’ll at least take your 6 tricks — you can’t go for too big a number.

Ideal preempts have a very high ODR; they will take a lot more tricks on offense than on defense. Some qualities that make for high ODR and ideal preempts:

- Solid suits with good intermediates/spot cards. When you have a long suit, its internal solidity is not going to matter on defense. But on offense, those jacks and tens and nines matter a lot. There’s a huge difference between KQ65432 and KQJT987.

- Values concentrated in your suit. Especially lesser honors like queens and jacks. A holding like Qx is likely to be worthless on offense, but on defense it will often take a trick.

- No aces, including in your suit. Aces are sure defensive tricks. A suit like KQJxxx is much better for a preempt than AQJTxx; the ODR is higher because the ace is likely to take a trick on defense.

- Void. Voids can throw off ODR. It’s harder to guess your ODR when you have a void, as you might have several defensive tricks via ruffing. The void could also mean the opponents’ suit isn’t splitting and partner has a trump trick or two.

- Single suited. The idea of a preempt is that you have only one suit you want to play in. When you have a second suit — especially a side 4-card major — you hand might play well somewhere else.

How High?

Generally, the level of your preempt will be based on the length of your suit. Here’s a simple rule of thumb:

6 cards Preempt at 2-level

7 cards Preempt at 3-level

8 cards Preempt at 4-level

These numbers are based on the Law of Total Tricks. Assuming your partner has a doubleton for you — which is about what you can expect on average opposite a preempt — you’re bidding at the level of your fit.

Preempts at the 2-level— known as weak-2s — are the most constructive and structured of preempts. They will usually be in the 5-10 HCP range, with no glaring flaws like voids or side 4-card majors. Preempts at the 3- and 4-levels can be a little wilder.

There’s no such thing as a weak-2 in clubs, since a 2♣ opening has a different meaning. So preemptive hands with a 6-card club suit have to either pass or open 3♣. It’s OK to open 3♣ with a 6-card suit. You just have to have the right hand and the right situation.

Should I Preempt?

When deciding whether to preempt, usually the decision is based on how far from the perfect preempt you should stray. You’re always going to preempt with ♠ KQJT962 ♥ 4 ♦ 832 ♣ 74. But when should you preempt with a less perfect hand — like ♠ Q63 ♥ AT86542 ♦ 2 ♣ J7? There are two key factors in these decisions: Seat and Vulnerability.

Vulnerability

Vulnerability is pretty obvious: when you’re vulnerable, you have to be more careful, because you can go for a big number. It’s not just your vulnerability that matters, but your opponents’ vulnerability too. When you are not vulnerable and your opponents are (known as favorable vulnerability) their game is worth 600 points. You can go down 3 tricks doubled and only go for 500 points. This is prime preempting time. When you are at equal vulnerability — either both vulnerable or both non-vulnerable — you can go down 2 tricks and see a profit: 300 vs a 400 game or 500 vs a 600 game. When you are at unfavorable vulnerability — you are red and they are white — you can only go down 1 trick. A second trick gets you to -500, more than their 400 game. So preempting has a lot to gain at favorable vulnerability and very little to gain at unfavorable vulnerability.

Seat

Seat is often overlooked, but it is almost as important as vulnerability. When you have a weak hand, someone at the table must have a strong hand. When you are the dealer, there are three other people at the table who could have that good hand, and two of them are your opponents. So you have ⅔ odds you’re preempting your opponents rather than partner. In second seat, the odds change, because your RHO has already passed, so he can’t have the big hand. Now it’s a 50-50 proposition whether you’re preempting an opponent or partner. In third seat, your partner has already passed, so you know where the big hand is — it’s on your left about to bid. Now it’s 100% you’re preempting an opponent.

So you should be most aggressive with your preempts in third seat, then in first seat, and most conservative in second seat. Preempts do not exist in fourth seat; there’s no point in trying to rob your opponents of bidding space when they have both passed. Jump opening bids in fourth seat show minimum opening hands (or just shy of an opening hand) with a good, long suit.

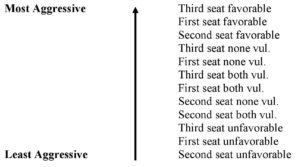

The Preempt Spectrum of Aggressiveness

Putting Seat and Vulnerability together, we get a spectrum, with third-seat favorable on one end and second-seat unfavorable on the other. It looks like this:

After They’ve Opened

Preempts are more effective as opening bids than as overcalls – the less information the opponents have had a chance to exchange before you jam up their auction, the better. But weak jump overcalls (WJOs) are also effective. The more information the opponents have exchanged, the less effective your preempt will be. So a WJO after an opening bid is more effective than after an opening and a response. A WJO after a 1♣ opening is more effective than after a 1NT opening (because the 1NT opening is so much more descriptive). A WJO is even more effective after a conventional opening bid, such as a Precision 1♣ or a 1m opening that could be a doubleton.

WJOs will look just like preemptive opening bids. Seat and vulnerability still matter. (Whether partner is a passed hand or not can also make a huge difference). Remember that a WJO has to be a jump. You would open 2♥ with ♠ x ♥ KQT9xx ♦ JTxx ♣ xx, but after a 1♠ opening by your RHO, 2♥ is not a jump, and so is not preemptive. If you want to preempt in hearts, you have to bid 3♥. That would be aggressive with this hand, but would be my choice at favorable vulnerability. Especially if partner is a passed hand.

Responding to a Preempt

With a Strong Hand

A preempt should define partner’s hand pretty well — she has a long suit and not a lot of strength outside of it. To have hopes of game, you need to have a very good hand. It’s not just a matter of HCP — it’s tricks. Don’t count on partner to have a lot of fillers for you — you’re going to need to provide the tricks in the other suits yourself. ♠ Kx ♥ QJxx ♦ KJxx ♣ AQJ is not a bad hand, but put it opposite a normal 2♠ opening bid, like ♠ AQJxxx ♥ xx ♦ xxxx ♣ x and game is not particularly good.

New suits in response to a preempt are forcing for one round. The preemptor should raise with three or Hx. Otherwise, she can rebid her suit with a minimum or do something else with a good hand — maybe bid NT or a new suit in which she has some values.

Over partner’s weak-2, responder can bid 2NT to ask about opener’s hand. This is a conventional bid, and opener responds with one of three bids:

- She returns to her suit with a minimum or nothing else to say.

- She bids a new suit with a good hand and a “feature” in the suit — an ace or king.

- She bids 3NT with a solid suit — AKQxxx

Alternatively, you can play Ogust, which uses these responses to 2NT:

- 3♣: bad hand, bad suit

- 3♦: bad hand, good suit

- 3♥: good hand, bad suit

- 3♠: good hand, good suit

I actually prefer ranking your hand 1-4, relative to what should be expected for your seat and position. 3♣ shows a 1, 3♦ a 2, etc.

Whether you play Feature or Ogust, with a solid suit (AKQxxx) opener should bid 3NT in response to the 2NT ask.

Asking for Keycards

A preemptor will not have 3 or more keycards. It makes sense to modify the responses to a keycard ask to cater to this. The response structure we use is 01122.

- 0 Keycards (partner can ask for the queen with the next step.)

- 1 Keycard without the queen of trumps

- 1 Keycard with the queen of trumps

- 2 Keycards without the queen of trumps

- 2 Keycards with the queen of trumps.

It also makes sense to modify the bid used to ask for keycards, as we have limited room and 4NT forces us to the 5-level. The bid we choose to use is 4♣. When preemptor’s suit is clubs, the keycard ask is 4♦. Responder can use this 4♣ keycard ask either directly over the preempt or after making a 2NT asking bid.

| Opener | Responder | Opener | Responder | |

| 2♠ | 2NT

|

3♣ | 4♦1 | |

| 3♦ | 4♣1

|

5♣2 | 6♣ | |

| 4♥2 | 4♠

|

|||

| 1. Keycard ask | 1. Keycard ask | |||

| 2. 1 without | 2. 2 without |

With a Weak Hand

Often when partner preempts you have a poor hand. That means the opponents have a lot of HCP — probably a game, maybe a slam. If you have a fit, you want to extend the preempt, taking up more of their bidding space. Remember, partner preempts assuming you have a doubleton in her suit; if you have more, you can raise the level of the preempt. Raises of preempts are non-forcing. (In response to preempts, the rule is RONF: Raises are the Only Non-Forcing bids.) The general guideline is to raise one level with 3-card support, two levels with 4-card support. So if partner opens 2♠ and you hold ♠ xxx ♥ xx ♦ Qxxx ♣ Jxxx, raise to 3♠. If you hold ♠ xxxx ♥ xx ♦ Jxxxx ♣ xx, raise to 4♠.

The Opponents Preempt

When the opponents preempt, your goal should not be perfection; you want to survive. Most of our normal rules apply:

- An overcall shows a good suit (at least 5 cards). Since their bid is weak and you’re coming in at a high level, you need at least a solid opening hand to overcall. The higher the level, the better your hand (and suit) should be.

- A 2NT overcall is similar to a 1NT overcall: a good 15-18 HCP, a solid stopper in their suit. Normal 2NT systems (Stayman, Transfers, etc.) are on. Note that this is NOT an Unusual 2NT situation; we need a natural strong notrump overcall.

- A 3NT overcall could be based on a very strong balanced hand, or it could be a “tricks” hand with a running suit (usually a minor) and a stopper in their suit.

- Doubles are normal takeout doubles. As the level rises, the strength required rises as well.

- One basic rule is No preempts over a preempt. If you jump over their preempt, you show a strong hand and very strong suit; partner can raise confidently with a singleton.

- With a hand that wants to penalize them, you must start with a pass, and count on partner to re-open with a takeout double.

- The corollary to this is that you want to be aggressive doubling in the balancing seat.

Lebensohl

Typically when responding to partner’s takeout double, you jump to show a good hand. That’s not practical when the opponents have opened at the 2-level, as your jump would both get the partnership too high and get past 3NT. The solution is to use Lebensohl. By giving up a natural 2NT bid, you gain the ability to make all your 3-level bids two ways:

| West | North | East | South |

| 2♠ | Dbl | Pass | 3♦ |

| West | North | East | South |

| 2♠

|

Dbl | Pass | 2NT* |

| Pass | 3♣* | Pass | 3♦ |

The first ways shows strength – about 9-11 HCP. The second way shows a weaker hand – fewer than 9 HCP. With a stronger hand you must force to game either by bidding game or by cuebidding opener’s suit.

Free Video

Five-card suits can be very powerful. Don’t overlook them.

The Box Principle

We can think of a bridge auction as an attempt to describe our hand as best we can. We can’t communicate a hand completely in one bid – it takes a series of bids to properly describe any hand. But we don’t have to start over every time it’s our turn to bid: each bid builds upon the description we have already started. Put another way, we can only describe our hand relative to what we have already shown. If we open 1NT, we cannot later show a hand with six hearts; that is inconsistent with the description we have started. If we open 1♣, we cannot show a balanced hand with 15-17 HCP (assuming our 1NT opening shows 15-17 HCP).

We call this concept the Box Principle. Every time you make a bid, you put your hand in a Box, and with each subsequent bid the Box becomes smaller. The important concept is that once you put your hand into a Box, hands outside of that Box are impossible, so all subsequent bids describe your hand within your Box.

Here’s an example. You hold ♠ Kx ♥ Qxxx ♦ AQxx ♣ QJx. A balanced hand with 14 HCP. You play a 1NT opening as 15-17, so you open 1♦.

Consider your Box at this point. Partner knows you have an opening hand, and that you have chosen to open 1♦. So you do not have a five-card major (unless you have 6+ diamonds) and you do not have a balanced hand that qualified for a 1NT or 2NT opening bid. Usually you will have at least four diamonds, and usually your diamonds will be as long or longer than your clubs. That’s a pretty big Box. You could have from 3 to 13 (well, maybe not 13) diamonds and from 12 to 22 or so HCP.

Partner responds 1♠, and you rebid 1NT. Your Box has gotten much smaller. Partner now knows:

- You have a balanced hand and 12-14 HCP.

- You do not have four spades (or you would have raised).

- You have at least four diamonds (you’ll only have three diamonds when 4=4=3=2, and you have denied four spades).

- Your clubs are not longer than your diamonds. Possible shapes in the minors are 4=4, 4=3, 4=2, 5=3 and 5=2.

Partner now bids 2♣, New Minor Forcing. He wants to know more about your hand. You have already described your hand quite well and your Box is pretty small. But within that Box you can give partner a little more information. Partner wants to know two things: a) what you have in the majors and b) whether you are minimum or maximum.

Our first goal in any auction is to support partner’s major suit. You have denied four spades by not raising immediately, and you cannot have a singleton or void in spades because your 1NT rebid showed a balanced hand. So the spade length in your Box is two or three. If you had three – the maximum support possible within your Box – you would raise partner’s spades. Since you only have a doubleton spade, you move onto the second priority: the other major. The maximum number of hearts within your Box is four – if you had more than that you would have opened 1♥. You have the maximum number of hearts, so that’s what you want to show.

Now to the second question: are you a minimum or a maximum? You have a minimum opening hand. But you have already shown that with your 1NT rebid. Your box is now 12-14 HCP; within that Box, your 14 HCP is a maximum. So the correct bid is a jump to 3♥.

The Box Principle applies in all areas of bidding. Once you deny a particular holding, you can subsequently show the next best holding possible (i.e., the best holding within your Box). This often applies to raising partner. Partner opens 1♠. When you don’t raise immediately, you deny (for the most part) three-card support. So at your next turn, you can support partner with honor-doubleton, as that is the maximum support possible within your Box. If you again do not support partner, at your next turn you can support with a small doubleton or a singleton honor, as those are the best holdings possible within your Box. Partner is not going to expect three-card support from you at this point – if you had that you would have raised the first time!

Where else might this apply? Let’s say we get into a control-bidding auction. Our style is to show either first- or second-round controls. So let’s say we agree on spades with a 3♠ bid and I make a control bid of 4♦. I am showing a control in diamonds, but also denying one in clubs. Now let’s say partner keeps control-bidding, and I bid 5♣. Since I already denied a first- or second-round control, I can’t be showing the ace or king of clubs. My delayed control-bid must show THIRD-round control – the best holding I could have within my Box.

Consider these two auctions:

| Opener | Responder | Opener | Responder | |

| 1♦ | 1♠ | 1♦ | 1♠

|

|

| 4♣ | 4♦ |

In the first auction, 4♣ is a Splinter, showing a very strong hand with four spades and a singleton or void in clubs. Something like ♠ KQxx ♥ AKx ♦ AQJxx ♣ x.

The second auction looks similar – a double jump. But consider the number of diamonds in Opener’s Box: he opened 1♦, so he must have 3+ diamonds. A singleton diamond is not possible, so this cannot be a Splinter. These “impossible Splinters” – jump bids that look like Splinters but cannot be because we have already promised length in the suit – show good hands with four-card support for partner and an excellent suit of our own. Something like ♠ KQxx ♥ Ax ♦ AKJxxx ♣ x. This hand could Splinter with 4♣, but the impossible Splinter is more descriptive.

Try thinking about your Box in complicated auctions. What does partner know about your hand, and based on that how can you best continue to describe your hand? Be careful in situations where you haven’t actually denied a certain holding. Consider these two auctions:

| Opener | Responder | Opener | Responder | |

| 1♠ | 2♣ | 1♠ | 2♣

|

|

| 2♥ | 2♠ | 2♥ | 3♣

|

|

| 3♥ | 3♠ |

The 2♣ bid does not deny three spades – it just sets a game force. So you cannot support partner with a doubleton; the 2♠ bid in the first auction must show three-card support. In the second auction, 3♠ certainly shows a doubleton, since you would have supported spades at your second call with three-card support.

The Box Principle

Here’s a great tool to help you think about the auction.

Fourth Suit Forcing

Fourth Suit Forcing is one of responder’s ways to create a game force.

Jacoby Transfers

Jacoby Transfers are an essential tool over a 1NT opening bid.

New Minor Forcing Part II

There’s more to New Minor Forcing than you think!